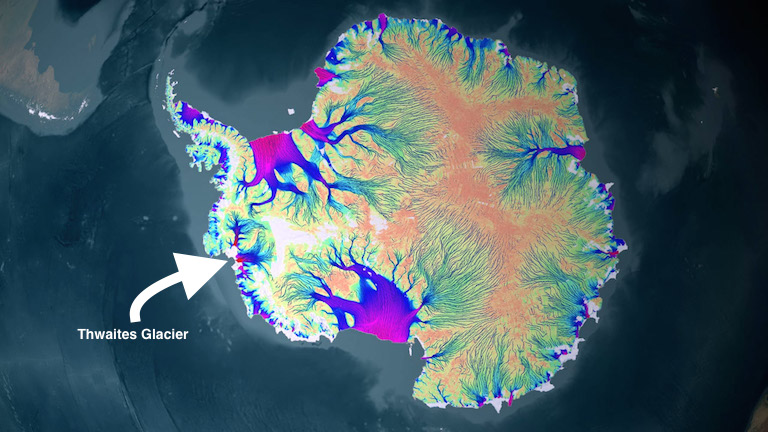

- NASA has found a 1,000-foot-tall cavity that’s two-thirds the size of Manhattan under the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica.

- The cavity is thought to have held 14 billion tons of ice that melted over the last three years.

- The melting Thwaites Glacier is responsible for 4% of annual global sea-level rise. If the entire glacier were to melt, it would raise sea levels by 2 feet.

- The unexpected gap below the ice signals we know less about melting glaciers than we thought, and that scientists are likely underestimating the speed of ice loss.

Scientists have spotted a never-before-seen hole under the Antarctic ice.

The cavity d is 984 feet tall and roughly two-thirds the size of Manhattan. It’s a sign that this part of the Antarctic ice sheet is melting faster than experts thought.

Antarctica is ringed by a skirt of ice sheets and floating ice shelves that provide a buffer between the ocean and the landlocked ice on the continent. These floating sheets “act like a dam,” as Ross Virginia, director of Dartmouth College’s Institute of Arctic Studies, previously told Business Insider. They prevent continental ice from flowing into the ocean, where it would eventually melt, leading global sea levels to rise.

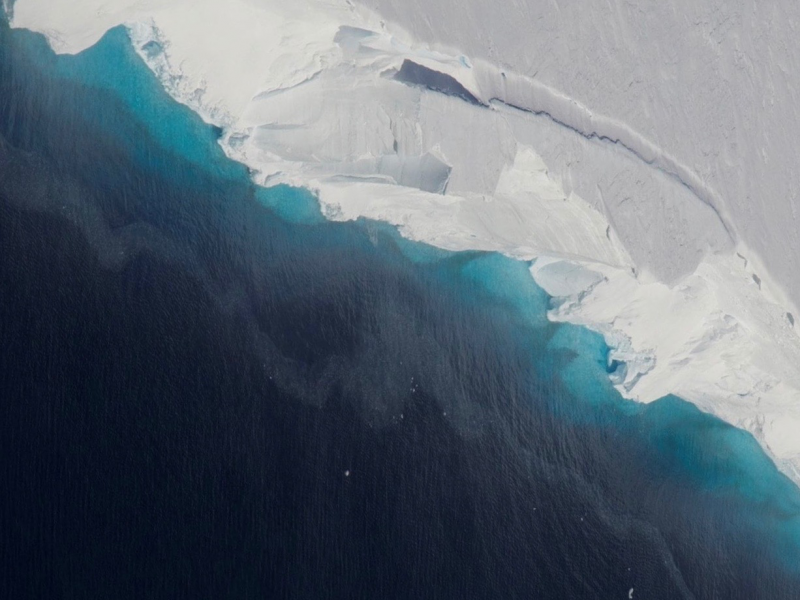

But as ocean temperatures increase, warmer water at the base of these ice sheets is causing them to melt from underneath. That melting gives rise to cavities like the this recently discovered gap.

"[The size of] a cavity under a glacier plays an important role in melting," Pietro Milillo, an environmental engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the lead author of the study, said in a press release. "As more heat and water get under the glacier, it melts faster."

The finding is just one indicator of the complex pattern of retreat and ice melt taking place at Thwaites Glacier, the authors of the new study said. Sections of Thwaites Glacier are retreating by up to 2,625 feet per year.

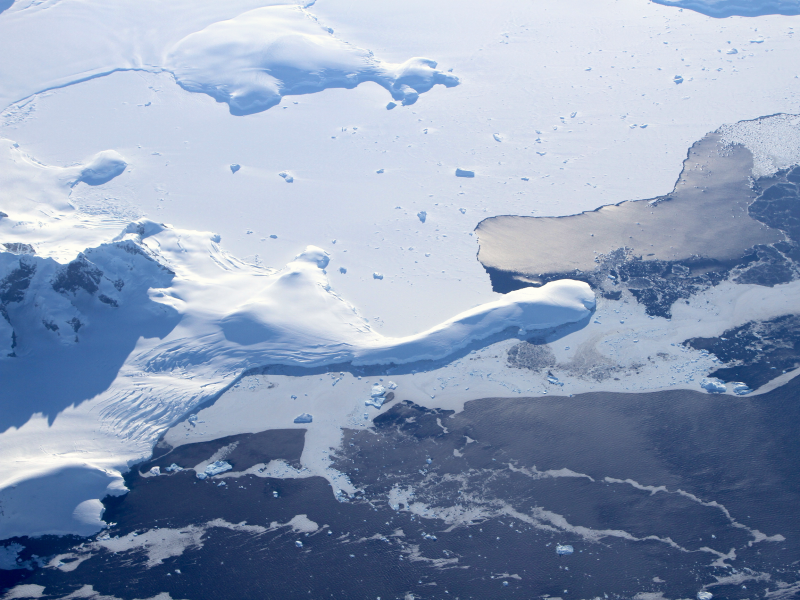

When ice sheets melt from below, they lose structural integrity. If they disintegrate, a surge of continental ice could flow into the ocean - an event called a "pulse," which would cause rapid sea-level rise.

Here's how scientists found the alarming cavity, and why Thwaites Glacier might be on a one-way road to its demise.

The Thwaites Glacier, an integral part of the Antarctic ice sheet, has an ice shelf that floats on water.

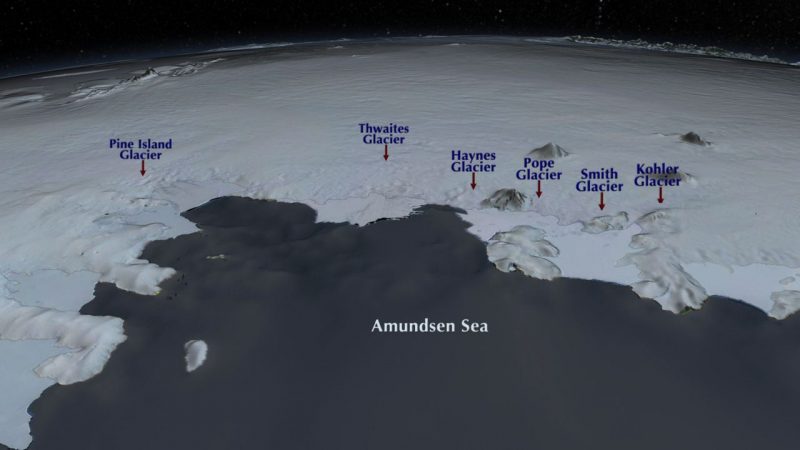

Thwaites Glacier is a large mass of ice born from snow that's been compressed over time. It's part of the Antarctic ice sheet - a large continental glacier that covers at least 20,000 square miles of land.

The Thwaites Glacier's floating ice shelf extends outward into the Amundsen Sea. Such shelves are characteristically flat and form a physical barrier around the continental ice, which slows ice sheets' movement and melting. Without them, sea-levels would rise faster.

The recently discovered cavity in the ice sheet appears to have grown rapidly thanks to the penetrating ebb and flow of warm ocean water underneath.

The more a glacier's undercarriage is exposed to the warming ocean waters, the more likely it is to see accelerated melting.

The recently discovered cavity is large enough to have held 14 billions tons of ice. Millilo and his study co-authors think most of that ice melted in the past three years.

“This is the ocean eating away at the ice,” Eric Rignot, a co-author of the study and a professor at the University of California, Irvine, told the New York Times.

"It's a direct impact of climate change on the glacier," Rignot added.

Thwaites's melting behavior bucked typical models and stunned NASA scientists. It suggests scientists are probably underestimating how fast ice is disappearing.

The new study suggests that scientists have a lot more to learn about the impact of warming oceans on ice shelves.

"The cavity is not the main target of my research," Milillo told Business Insider. "What is surprising about the cavity is that it means ocean-ice interactions are more complex than we previously understood. This is the new message here."

NASA keeps tabs on the Thwaites ice shelf using ice-penetrating radar. That's how it discovered the large cavity.

The agency's Operation IceBridge project, which began in 2010, flies over the North and South Poles each year to collect data via airborne instruments and observations. Its findings supplement NASA's satellite data, and allow scientists to analyze different glaciers' heights and melting speeds.

Scientists also track a glacier's grounding line: the spot where the continental ice lifts off the ground and starts to float on the water.

To understand a glacier's grounding line, think of a spit of land that extends past a cliff's edge into the air - it's the same concept with glaciers, except instead of air, the ice is floating on water.

Many of Antarctica's glaciers extend far beyond their grounding lines into the ocean, sometimes for miles, according to NASA. But as global temperatures rise (and oceans absorb much of that heat), glaciers' grounding lines are moving inland, leaving more ice floating on water.

Thwaites's grounding line moved almost 9 miles inward between 1992 and 2011, according to a 2014 study.

Floating glaciers are less stable, since they're prone to calving events in which parts of the glacier fall into the ocean. Glaciers on water also melt faster than ice on land does.

About the size of Florida, the melting Thwaites Glacier is responsible for roughly 4% of global sea-level rise.

Antarctica's ice sheet could cover the surface area of the United States and Mexico combined, according to Columbia University's Earth Institute.

If the whole Thwaites Glacier melted, it would result in a worldwide sea-level rise of more than 2 feet. What's more, Thwaites prevents its neighbor glaciers from flowing into the oceans, too. If one goes, they could all go - and that chain-reaction would raise sea levels an additional 8 feet.

Scientists studying melting ice are particularly interested in the area of the western Antarctic ice sheet where the Thwaites Glacier is located.

Because this region's glaciers have grounding lines that are below sea level, it's easier for the ocean to pound those lines with warm water, according to NASA.

Milillo said the glaciers seem to be responding to what's happening in the ocean in disproportionate ways.

"That's why it's difficult to predict, and why new need satellites to capture the tiniest changes in the glaciers," he said.

Many studies suggest that this part of western Antarctica's ice sheet has begun an irreversible march towards its own demise.

The amount of ice this part of Antarctica has lost to the ocean has increased by 77% since 1973, one of Rignot's other studies showed. Half of that increase happened between 2003 and 2009.

That increased quantity of ice floating out to sea, coupled with accelerated melting, are indicators of an eventual collapse. Unless something changes, the Thwaites Glacier is on pace to collapse in as little as 100 to 200 years from now, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

"How fast will this happen is the most important question in glaciology," Milillo said. "We're trying to understand the timescale of this thing."